Between Stockholm Syndrome and Lima Syndrome

Part 45: The Law of Unintended Consequences in the Religious Industrial Complex

Those who do not move, do not notice their chains.

-ROSA LUXEMBURG (1871-1919)

The problem is that many do not mind to be chained at all. As stated in Part 12 (What is God's Religion?), the word "religion" derives from the word religare (Latin) which means 'to bind.' Thus if we only show people how oppressive religion can be, they may hopefully open their eyes and seek freedom. Nothing could be further than the truth.

More than 2,300 years had passed since Plato (428-348 BCE) warned us about mistaking shadows on the walls for real objects, in his famous Allegory of the Cave. Yet the religious industrial complex is alive and well. Even stronger than ever. In a culture that claims to value freedom above anything else, many do not mind to be chained. They want to be chained.

It should not be surprising. In 1843, German philosopher and economist Karl Marx warned that religion is the opium of the people in his classic, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Well, what is wrong with opium? According to www.opium.org, "(a)lthough the side effects of opium that are felt short-term such as euphoria or sedation may be comforting, as tolerance develops, even these side effects will diminish and the negative aspects of the opium use will quickly begin to set in." Marx is hardly alone. "One of the curses of ideologies and organized beliefs is the comfort, the deadly gratification they offer," wrote J. Krishnamurti in Commentaries on Living (1956). "They put us to sleep, and in the sleep we dream, and the dream becomes action. How easily we are distracted! And most of us want to be distracted … and distractions becomes a necessity, they become more important than what is."

Bondage, shadows, opium, comfort, gratification, dreams, distractions; what could be better? The smashing success of the religious industrial complex should not surprise us. Not only does religion comfort the masses. In fact, the opposite—i.e. freedom from religion and beliefs—can be painfully torturous for many. Take religion away, and you take away the security blanket, the opium, the training wheels, the crutches. Dealing with withdrawal symptoms is no picnic.

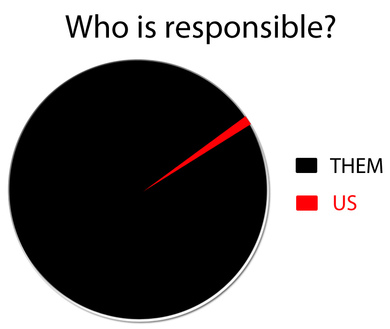

"Freedom aggravates at least as much as it alleviates frustration," wrote Eric Hoffer in The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (1951). "Freedom of choice places the whole blame of failure on the shoulders of the individual." Then, furthermore: "Unless a man has the talents to make something of himself, freedom is an irksome burden… We join a mass movement to escape individual responsibility, or, in the words of the ardent young Nazi, "to be free from freedom.""

Thus freedom from religion demands individual responsibility and accountability—a tall order for many. No more excuses. No more saviors of any kind. No more rewards and punishments. No more redemption. No more twenty-one virgins waiting in paradise. One is on his own—fully responsible and accountable for his deeds. That's why agnostics and atheists tend to take religion much more seriously than theists. Case in point: at the age of sixteen, British philosopher, logician and mathematician, Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) flatly declared: "(m)y whole religion is this: do every duty, and expect no reward for it, either here or hereafter." Observed another British, physician Jonathan Miller (b. 1934): "In some awful, strange, paradoxical way, atheists tend to take religion more seriously than the practitioners."

Therefore the positive correlation between religion and morality is a myth, an illusion. Allow me to repeat the comparison of four past Southeast Asian rulers. Ferdinand Marcos, a practicing Catholic, ruled the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. Suharto, a practicing Muslim, ruled Indonesia from 1967 to 1998. Lee Kuan Yew, a self-proclaimed non-believer, ruled Singapore from 1959 to 1990. Thaksin Shinawatra, a practicing Buddhist, ruled Thailand from 2001 to 2006. Three among these four strongmen were forced to resign and eventually convicted of corruption, though they never served time. (Obviously, proceed from corruption come in handy to retain the best lawyers in the country or to live lavishly in exile.) One ruler is exceptionally known as "Mr. Clean" until his death in 2015 however. Everyone knows who was "Mr. Clean."

One may argue that even though religion has failed to curb corruption, it may make believers more tolerant and pacifist. We shall see. As stated in Part 36 (Being in the "Zone"), in an op-ed in The Los Angeles Times (October 30, 2015), Phil Zuckerman begs to differ. In Think Religion Makes Society Less Violent?, he outlines that the most secular societies (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Czech Republic, Estonia, Japan, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Germany, South Korea, New Zealand, Australia, Vietnam, Hungary, China and Belgium) fare the best in terms of crime rates, prosperity, equality, freedom, democracy, women's rights, human rights, educational attainment and life expectancy. (With poor human rights records, Vietnam and China are exceptions.) On the other hand, the most religious societies (Nigeria, Uganda, the Philippines, Pakistan, Morocco, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, El Salvador, Colombia, Senegal, Malawi, Indonesia, Brazil, Peru, Jordan, Algeria, Ghana, Venezuela, Mexico and Sierra Leone) tend to be the most problem-ridden in terms of high violent crime rates, high infant mortality rates, high poverty rates and high rates of corruption.

Thus the law of unintended consequences in the religious industrial complex: religion does not necessarily improve individual responsibility and accountability.

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

-ROSA LUXEMBURG (1871-1919)

The problem is that many do not mind to be chained at all. As stated in Part 12 (What is God's Religion?), the word "religion" derives from the word religare (Latin) which means 'to bind.' Thus if we only show people how oppressive religion can be, they may hopefully open their eyes and seek freedom. Nothing could be further than the truth.

More than 2,300 years had passed since Plato (428-348 BCE) warned us about mistaking shadows on the walls for real objects, in his famous Allegory of the Cave. Yet the religious industrial complex is alive and well. Even stronger than ever. In a culture that claims to value freedom above anything else, many do not mind to be chained. They want to be chained.

It should not be surprising. In 1843, German philosopher and economist Karl Marx warned that religion is the opium of the people in his classic, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Well, what is wrong with opium? According to www.opium.org, "(a)lthough the side effects of opium that are felt short-term such as euphoria or sedation may be comforting, as tolerance develops, even these side effects will diminish and the negative aspects of the opium use will quickly begin to set in." Marx is hardly alone. "One of the curses of ideologies and organized beliefs is the comfort, the deadly gratification they offer," wrote J. Krishnamurti in Commentaries on Living (1956). "They put us to sleep, and in the sleep we dream, and the dream becomes action. How easily we are distracted! And most of us want to be distracted … and distractions becomes a necessity, they become more important than what is."

Bondage, shadows, opium, comfort, gratification, dreams, distractions; what could be better? The smashing success of the religious industrial complex should not surprise us. Not only does religion comfort the masses. In fact, the opposite—i.e. freedom from religion and beliefs—can be painfully torturous for many. Take religion away, and you take away the security blanket, the opium, the training wheels, the crutches. Dealing with withdrawal symptoms is no picnic.

"Freedom aggravates at least as much as it alleviates frustration," wrote Eric Hoffer in The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (1951). "Freedom of choice places the whole blame of failure on the shoulders of the individual." Then, furthermore: "Unless a man has the talents to make something of himself, freedom is an irksome burden… We join a mass movement to escape individual responsibility, or, in the words of the ardent young Nazi, "to be free from freedom.""

Thus freedom from religion demands individual responsibility and accountability—a tall order for many. No more excuses. No more saviors of any kind. No more rewards and punishments. No more redemption. No more twenty-one virgins waiting in paradise. One is on his own—fully responsible and accountable for his deeds. That's why agnostics and atheists tend to take religion much more seriously than theists. Case in point: at the age of sixteen, British philosopher, logician and mathematician, Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) flatly declared: "(m)y whole religion is this: do every duty, and expect no reward for it, either here or hereafter." Observed another British, physician Jonathan Miller (b. 1934): "In some awful, strange, paradoxical way, atheists tend to take religion more seriously than the practitioners."

Therefore the positive correlation between religion and morality is a myth, an illusion. Allow me to repeat the comparison of four past Southeast Asian rulers. Ferdinand Marcos, a practicing Catholic, ruled the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. Suharto, a practicing Muslim, ruled Indonesia from 1967 to 1998. Lee Kuan Yew, a self-proclaimed non-believer, ruled Singapore from 1959 to 1990. Thaksin Shinawatra, a practicing Buddhist, ruled Thailand from 2001 to 2006. Three among these four strongmen were forced to resign and eventually convicted of corruption, though they never served time. (Obviously, proceed from corruption come in handy to retain the best lawyers in the country or to live lavishly in exile.) One ruler is exceptionally known as "Mr. Clean" until his death in 2015 however. Everyone knows who was "Mr. Clean."

One may argue that even though religion has failed to curb corruption, it may make believers more tolerant and pacifist. We shall see. As stated in Part 36 (Being in the "Zone"), in an op-ed in The Los Angeles Times (October 30, 2015), Phil Zuckerman begs to differ. In Think Religion Makes Society Less Violent?, he outlines that the most secular societies (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Czech Republic, Estonia, Japan, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Germany, South Korea, New Zealand, Australia, Vietnam, Hungary, China and Belgium) fare the best in terms of crime rates, prosperity, equality, freedom, democracy, women's rights, human rights, educational attainment and life expectancy. (With poor human rights records, Vietnam and China are exceptions.) On the other hand, the most religious societies (Nigeria, Uganda, the Philippines, Pakistan, Morocco, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, El Salvador, Colombia, Senegal, Malawi, Indonesia, Brazil, Peru, Jordan, Algeria, Ghana, Venezuela, Mexico and Sierra Leone) tend to be the most problem-ridden in terms of high violent crime rates, high infant mortality rates, high poverty rates and high rates of corruption.

Thus the law of unintended consequences in the religious industrial complex: religion does not necessarily improve individual responsibility and accountability.

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed