Between Stockholm Syndrome and Lima Syndrome

Part 22: There is Something Immoral in Immortality

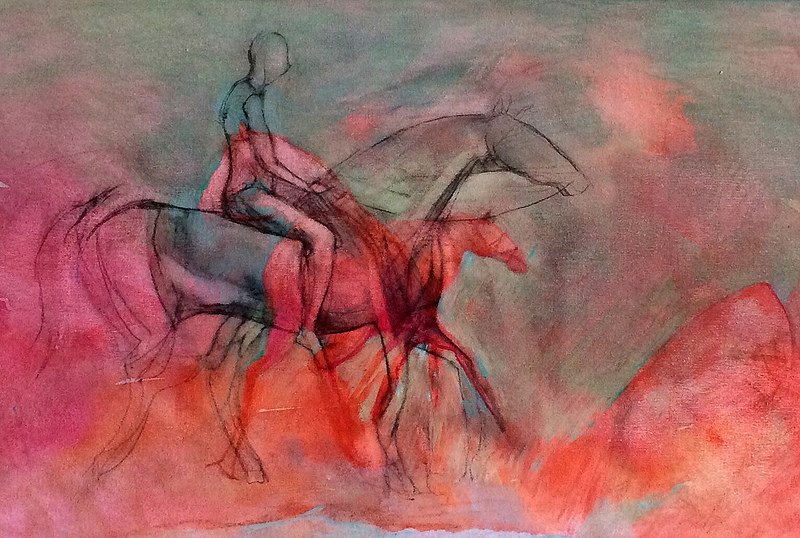

A man named Sei Weng owned a beautiful mare which was praised far and wide. One day this beautiful horse disappeared. The people of his village offered sympathy to Sei Weng for his great misfortune. Sei Weng said simply, "That's the way it is."

A few days later the lost mare returned, followed by a beautiful wild stallion. The village congratulated Sei Weng for his good fortune. He said, "That's the way it is." Some time later, Sei Weng's only son, while riding the stallion, fell off and broke his leg. The village people once again expressed their sympathy at Sei Weng's misfortune. Sei Weng again said, "That's the way it is."

Soon thereafter, war broke out and all the young men of the village except Sei Weng's lame son were drafted and were killed in battle. The village people were amazed as Sei Weng's good luck. His son was the only young man left alive in the village. But Sei Weng kept his same attitude: despite all the turmoil, gains and losses, he gave the same reply, "That's the way it is."

The horse that went away is the horse that came back—that's the way it is. The aforementioned Taoist parable illustrates the non-duality of fortune and misfortune, gain and loss, life and death poignantly. More importantly, it underlines the importance of a counter balance—something does not exist without its opposite. "Truth can be reached only through the comprehension of opposites," wrote Kakuzo Okakura (1862-1913) in The Book of Tea (1906). Note the emphasis on comprehension—a deeper and more comprehensive level of understanding. The brutal truth is that no matter how the religion-industrial complex has been sugarcoating death at all costs to sell their Zoroastrian afterlife contractual program merely in order to assuage the fear of death, there can never be life without death. On a species level. On a personal level.

Even on a cellular level, death and renewal can even be described as a prerequisite to life—as cited by science writer Guy Murchie (1907-1997) in his illuminating The Seven Mysteries of Life (1978). Based on radioisotope tracings of numerous chemicals that continuously enter and leave the human body, Dr. Paul C. Aebersold of the Oak Ridge Atomic Research Center concluded that about 98 percent of the 10 octillion (thus a 1 with 28 zeroes) atoms in the average human body are replaced annually. The crystals of bones are continually dissolving and reforming; the stomach's lining replaces itself every five days; skin wear and tear is completely retreaded in about a month; and a new liver is formed every six weeks. Chemistry professor Donald Hatch Andrews of John Hopkins University even estimated that one's physical body is completely renewed down to the very last atom within about five years. This constant change is normal.

What is abnormal is cancer, "the emperor of all maladies." Cancer is caused by abnormal cell growth that potentially invades or spreads to other parts or organs. Only recently have scientists understood the fundamental difference between a normal and a cancerous cell. As argued by Robert Hazen and Maxine Singer in Why Aren't Black Holes Black? (1997), the great irony of cancer is that it results from the failure of cells … to die. A normal cell is supposed to age and die naturally. On the other hand, a cancerous cell is immortal because its regulating clock is either turned off, constantly reset, or just ignored.

Therefore, whether on a cellular, personal or species level, death is inevitable. Blindly pursuing immortality—either by blowing oneself up for heavenly rewards of 21 virgins or through the ridiculous process of cryopreservation (low-temperature preservation of the human body with the hope it may be resuscitated in the future) does not only reflect selfishness and megalomania; it reflects perversion and immorality.

The truth remains that our life in this little corner of the universe is but fleeting and transitory. Because of it—not in spite of it—this temporariness should make us realize that life is even more precious and beautiful. Carpe diem. There can never be any justification to sacrifice life merely as a dubious investment to secure a better afterlife. "I have little confidence in any enterprise or business or investment that promises dividends only after the death of the stockholders," argued author Robert Ingersoll (1833-1899).

Death—as illustrated by the Roman emperor philosopher Marcus Aurelius (121-180) in his Book 4 of Meditations—is indeed the Great Equalizer: How many doctors have died, after furrowing their brows over how many deathbeds. How many astrologers, after pompous forecasts about others' ends. How many philosophers, after endless disquisitions on death and immortality. How many warriors, after inflicting thousands of casualties themselves. How many tyrants, after abusing the power of life and death atrociously, as if they were themselves immortal. How many whole cities have met their end: Helike, Pompeii, Herculaneum, and countless others.

Further on, without mincing his words: Human lives are brief and trivial. Yesterday a blob of semen; tomorrow embalming fluid, ash. To pass through this brief life as nature demands. To give it up without complaint. Like an olive that ripens and falls. Praising its mother, thanking the tree it grew on.

Thus—the yin and yang of life, and inevitable death. "Those with their great desire to go on living;" Italian astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) once said, "they do not reflect that if men were immortal, they themselves would never have come into the world."

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

A few days later the lost mare returned, followed by a beautiful wild stallion. The village congratulated Sei Weng for his good fortune. He said, "That's the way it is." Some time later, Sei Weng's only son, while riding the stallion, fell off and broke his leg. The village people once again expressed their sympathy at Sei Weng's misfortune. Sei Weng again said, "That's the way it is."

Soon thereafter, war broke out and all the young men of the village except Sei Weng's lame son were drafted and were killed in battle. The village people were amazed as Sei Weng's good luck. His son was the only young man left alive in the village. But Sei Weng kept his same attitude: despite all the turmoil, gains and losses, he gave the same reply, "That's the way it is."

The horse that went away is the horse that came back—that's the way it is. The aforementioned Taoist parable illustrates the non-duality of fortune and misfortune, gain and loss, life and death poignantly. More importantly, it underlines the importance of a counter balance—something does not exist without its opposite. "Truth can be reached only through the comprehension of opposites," wrote Kakuzo Okakura (1862-1913) in The Book of Tea (1906). Note the emphasis on comprehension—a deeper and more comprehensive level of understanding. The brutal truth is that no matter how the religion-industrial complex has been sugarcoating death at all costs to sell their Zoroastrian afterlife contractual program merely in order to assuage the fear of death, there can never be life without death. On a species level. On a personal level.

Even on a cellular level, death and renewal can even be described as a prerequisite to life—as cited by science writer Guy Murchie (1907-1997) in his illuminating The Seven Mysteries of Life (1978). Based on radioisotope tracings of numerous chemicals that continuously enter and leave the human body, Dr. Paul C. Aebersold of the Oak Ridge Atomic Research Center concluded that about 98 percent of the 10 octillion (thus a 1 with 28 zeroes) atoms in the average human body are replaced annually. The crystals of bones are continually dissolving and reforming; the stomach's lining replaces itself every five days; skin wear and tear is completely retreaded in about a month; and a new liver is formed every six weeks. Chemistry professor Donald Hatch Andrews of John Hopkins University even estimated that one's physical body is completely renewed down to the very last atom within about five years. This constant change is normal.

What is abnormal is cancer, "the emperor of all maladies." Cancer is caused by abnormal cell growth that potentially invades or spreads to other parts or organs. Only recently have scientists understood the fundamental difference between a normal and a cancerous cell. As argued by Robert Hazen and Maxine Singer in Why Aren't Black Holes Black? (1997), the great irony of cancer is that it results from the failure of cells … to die. A normal cell is supposed to age and die naturally. On the other hand, a cancerous cell is immortal because its regulating clock is either turned off, constantly reset, or just ignored.

Therefore, whether on a cellular, personal or species level, death is inevitable. Blindly pursuing immortality—either by blowing oneself up for heavenly rewards of 21 virgins or through the ridiculous process of cryopreservation (low-temperature preservation of the human body with the hope it may be resuscitated in the future) does not only reflect selfishness and megalomania; it reflects perversion and immorality.

The truth remains that our life in this little corner of the universe is but fleeting and transitory. Because of it—not in spite of it—this temporariness should make us realize that life is even more precious and beautiful. Carpe diem. There can never be any justification to sacrifice life merely as a dubious investment to secure a better afterlife. "I have little confidence in any enterprise or business or investment that promises dividends only after the death of the stockholders," argued author Robert Ingersoll (1833-1899).

Death—as illustrated by the Roman emperor philosopher Marcus Aurelius (121-180) in his Book 4 of Meditations—is indeed the Great Equalizer: How many doctors have died, after furrowing their brows over how many deathbeds. How many astrologers, after pompous forecasts about others' ends. How many philosophers, after endless disquisitions on death and immortality. How many warriors, after inflicting thousands of casualties themselves. How many tyrants, after abusing the power of life and death atrociously, as if they were themselves immortal. How many whole cities have met their end: Helike, Pompeii, Herculaneum, and countless others.

Further on, without mincing his words: Human lives are brief and trivial. Yesterday a blob of semen; tomorrow embalming fluid, ash. To pass through this brief life as nature demands. To give it up without complaint. Like an olive that ripens and falls. Praising its mother, thanking the tree it grew on.

Thus—the yin and yang of life, and inevitable death. "Those with their great desire to go on living;" Italian astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) once said, "they do not reflect that if men were immortal, they themselves would never have come into the world."

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed