Between Stockholm Syndrome and Lima Syndrome

Part 27: A Familiar Story that is Untrue is More Comforting than an Unfamiliar Story that is True

There are one hundred and ninety-three living species of monkeys and apes.

One hundred and ninety-two of them are covered with hair.

The exception is a naked ape self-named Homo sapiens.

-DESMOND MORRIS, The Naked Ape (1967)

The fact that Homo sapiens is the only hairless species among monkeys and apes seems to cause them having a soft spot for stories, narratives, and gossips. It seems that the less hair a species has, the more it is addicted to narratives. How so? What is the correlation between hair and narratives anyway?

Chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, baboons, bonobos (the closest extant relative to humans, who may share 98.6% of their DNA with us) all have hair, but no taste whatsoever for narratives. Sure, they may have some primordial language communication system expressed in screams and grunts but not to the sophisticated level of human language. On the other hand we, Homo sapiens, are the opposite: hairless but with a knack to develop language and to structure narratives. The negative correlation between hair and the thirst for narratives cannot be ignored.

The explanation for this phenomenon may be buried in Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language (1998) by psychologist Robin Dunbar. Gossip, as defined in the Oxford Dictionary, is: "casual or unconstrained conversation or reports about other people, typically involving details that are not confirmed as being true." True or not, gossip satisfies human social instincts, especially that unquenchable thirst for narratives. Dunbar looks at gossip as an "instrument of social order and cohesion—much like the endless grooming with which our primate cousins tend to their social relationships."

According to Dunbar, apes and monkeys, humanity's closest kin, differ from other animals in the intensity of these relationships. All their grooming is not so much about cleaning each other of dead skin, debris, ticks, fleas, lice, and lice eggs (which groomers immediately eat as those fleas and lice are a protein source anyway), as it is about "cementing bonds, making friends, and influencing fellow primates." But for early humans—the most economic animal on earth—grooming as a way to social survival was too cumbersome. Given their large social groups of hundreds or so, early humans would have had to spend a significant chunk of precious time in the parasite removal business of grooming each other. After all, among early humans, limited amount of hair seemed to produce only limited amount of ticks, fleas, and lice.

Enter language. Dunbar concludes that, "humans developed language to serve the same purpose, but far more efficiently. It seems there is nothing idle about chatter, which holds together a diverse, dynamic group—whether of hunter-gatherers, soldiers, or workmates."

In short, whereas apes and monkeys form social bonding through grooming each other, humans do the same thing through telling gossips, stories, narratives. Whereas the social currency for apes and monkeys are ticks, fleas, lice; for humans it is gossips, stories, and narratives. Indeed anthropologists Levi-Strauss and Mircea Eliade have long argued that one of the earliest roles of the shaman or sage was to tell stories which provided "symbolic solutions to contradictions which could not be solved empirically." It did not really matter whether the protagonists and actors in those stories—whether gods, ghosts, dragons, unicorns, mermaids, centaurs, goblins—exist or not. That's beside the point. The most important thing was that those ancient mythologies and symbolism fulfill human desperate need for gossips, narratives, social taboos, explanations, even self-fulfilling prophecies.

Whereas there is an infinite supply of ticks, fleas, and lice for monkeys and apes, there is only a finite supply of stories for humans. Repetitions after repetitions became unavoidable. Therefore a familiar story that is untrue is much more comforting, compelling, and validating than an unfamiliar story that is true. Familiarity does trump truthfulness. The Great Stories, as eloquently described by Indian novelist Arundhati Roy, "are the ones you have heard and want to hear again. The ones you can enter anywhere and inhabit comfortably… They don't surprise you with the unforeseen. They are as familiar as the house you live in. Or the smell of your lover's skin. You know how they end, yet you listen as though you don't. In the Great Stories you know who lives, who dies, who finds love, who doesn't. And yet you want to know again. THAT is their mystery and magic." I don't even know how many dozen times I watched Rodgers & Hammerstein's The Sounds of Music (1965) when my daughter was between 8 and 12 years old.

Familiarity breeds complacency and credulity. As argued by American microbiologist and environmentalist René Jules Dubos (1901-1982), while ideally "man should remain receptive to new stimuli and new situations in order to continue to develop; in practice the ability to perceive the external worlds with freshness decrease as the senses and the mind are increasingly conditioned in the course of life." Not only does familiarity influences perception, but it diminishes our critical thinking and conscious attention with which we perform our acts. Not only we became conditioned to act on autopilot, we are conditioned to think this is normal! Thus our mind became hopelessly desensitized and extremely vulnerable to propaganda, pseudo-science, disinformation, and 1001 religious claims.

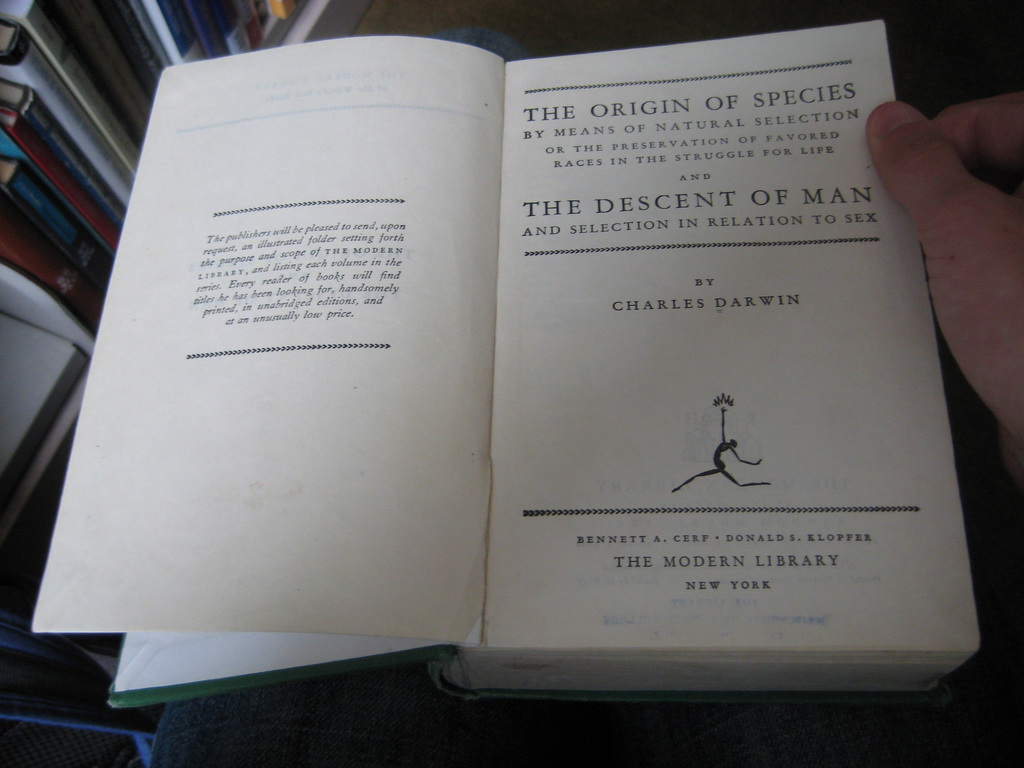

Thanks to this strong inclination to imitate whatever is familiar regardless of whether it's true or not, we became extremely vulnerable to Joseph Goebbels's maxim as stated in Part 25 (What If Adam had not Eaten an Apple?): "If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it." That's why so many among us, in this 21st Century, still take every single word in a particular holy book literally. Curiously, the definition of to ape in the Oxford Dictionary is: "(to) imitate the behavior or manner of (someone or something), especially in an absurd or unthinking way." What better way to underline this bitter truth by quoting Desmond Morris again, "I viewed my fellow man not as a fallen angel, but as a risen ape."

There is still reason to be optimistic.

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

One hundred and ninety-two of them are covered with hair.

The exception is a naked ape self-named Homo sapiens.

-DESMOND MORRIS, The Naked Ape (1967)

The fact that Homo sapiens is the only hairless species among monkeys and apes seems to cause them having a soft spot for stories, narratives, and gossips. It seems that the less hair a species has, the more it is addicted to narratives. How so? What is the correlation between hair and narratives anyway?

Chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, baboons, bonobos (the closest extant relative to humans, who may share 98.6% of their DNA with us) all have hair, but no taste whatsoever for narratives. Sure, they may have some primordial language communication system expressed in screams and grunts but not to the sophisticated level of human language. On the other hand we, Homo sapiens, are the opposite: hairless but with a knack to develop language and to structure narratives. The negative correlation between hair and the thirst for narratives cannot be ignored.

The explanation for this phenomenon may be buried in Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language (1998) by psychologist Robin Dunbar. Gossip, as defined in the Oxford Dictionary, is: "casual or unconstrained conversation or reports about other people, typically involving details that are not confirmed as being true." True or not, gossip satisfies human social instincts, especially that unquenchable thirst for narratives. Dunbar looks at gossip as an "instrument of social order and cohesion—much like the endless grooming with which our primate cousins tend to their social relationships."

According to Dunbar, apes and monkeys, humanity's closest kin, differ from other animals in the intensity of these relationships. All their grooming is not so much about cleaning each other of dead skin, debris, ticks, fleas, lice, and lice eggs (which groomers immediately eat as those fleas and lice are a protein source anyway), as it is about "cementing bonds, making friends, and influencing fellow primates." But for early humans—the most economic animal on earth—grooming as a way to social survival was too cumbersome. Given their large social groups of hundreds or so, early humans would have had to spend a significant chunk of precious time in the parasite removal business of grooming each other. After all, among early humans, limited amount of hair seemed to produce only limited amount of ticks, fleas, and lice.

Enter language. Dunbar concludes that, "humans developed language to serve the same purpose, but far more efficiently. It seems there is nothing idle about chatter, which holds together a diverse, dynamic group—whether of hunter-gatherers, soldiers, or workmates."

In short, whereas apes and monkeys form social bonding through grooming each other, humans do the same thing through telling gossips, stories, narratives. Whereas the social currency for apes and monkeys are ticks, fleas, lice; for humans it is gossips, stories, and narratives. Indeed anthropologists Levi-Strauss and Mircea Eliade have long argued that one of the earliest roles of the shaman or sage was to tell stories which provided "symbolic solutions to contradictions which could not be solved empirically." It did not really matter whether the protagonists and actors in those stories—whether gods, ghosts, dragons, unicorns, mermaids, centaurs, goblins—exist or not. That's beside the point. The most important thing was that those ancient mythologies and symbolism fulfill human desperate need for gossips, narratives, social taboos, explanations, even self-fulfilling prophecies.

Whereas there is an infinite supply of ticks, fleas, and lice for monkeys and apes, there is only a finite supply of stories for humans. Repetitions after repetitions became unavoidable. Therefore a familiar story that is untrue is much more comforting, compelling, and validating than an unfamiliar story that is true. Familiarity does trump truthfulness. The Great Stories, as eloquently described by Indian novelist Arundhati Roy, "are the ones you have heard and want to hear again. The ones you can enter anywhere and inhabit comfortably… They don't surprise you with the unforeseen. They are as familiar as the house you live in. Or the smell of your lover's skin. You know how they end, yet you listen as though you don't. In the Great Stories you know who lives, who dies, who finds love, who doesn't. And yet you want to know again. THAT is their mystery and magic." I don't even know how many dozen times I watched Rodgers & Hammerstein's The Sounds of Music (1965) when my daughter was between 8 and 12 years old.

Familiarity breeds complacency and credulity. As argued by American microbiologist and environmentalist René Jules Dubos (1901-1982), while ideally "man should remain receptive to new stimuli and new situations in order to continue to develop; in practice the ability to perceive the external worlds with freshness decrease as the senses and the mind are increasingly conditioned in the course of life." Not only does familiarity influences perception, but it diminishes our critical thinking and conscious attention with which we perform our acts. Not only we became conditioned to act on autopilot, we are conditioned to think this is normal! Thus our mind became hopelessly desensitized and extremely vulnerable to propaganda, pseudo-science, disinformation, and 1001 religious claims.

Thanks to this strong inclination to imitate whatever is familiar regardless of whether it's true or not, we became extremely vulnerable to Joseph Goebbels's maxim as stated in Part 25 (What If Adam had not Eaten an Apple?): "If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it." That's why so many among us, in this 21st Century, still take every single word in a particular holy book literally. Curiously, the definition of to ape in the Oxford Dictionary is: "(to) imitate the behavior or manner of (someone or something), especially in an absurd or unthinking way." What better way to underline this bitter truth by quoting Desmond Morris again, "I viewed my fellow man not as a fallen angel, but as a risen ape."

There is still reason to be optimistic.

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed