Between Stockholm Syndrome and Lima Syndrome

Part 28: Reflection on Today's World Hotspot

A donkey with a load of holy books is still a donkey.

-SUFI PROVERB

The relentless inclination to ape or imitate among Homo sapiens may be attributed to how one learns in a certain culture. As discussed in Part 23 (Do We Choose a Belief or Does a Belief Choose Us?), statistically speaking, one's religion depends very much on where he or she was born; i.e. a Sunni if born in Afghanistan; a Southern Baptist if in Atlanta; a Catholic if in Buenos Aires; a Hindu if in Mumbai; a Mormon if in Salt Lake City; and so on. The golden rule of real estate (Location, Location, Location) applies.

However, there is still another predictive factor: learning styles. We all learn differently. People who are reared in different cultures also learn to learn different things differently, even if they learn from the same book. All other things being equal, ceteris paribus, even within the same religion, different cultures have different preferred modes of learning, whether by memory (verbal-linguistic), cognition (logical-mathematical), active participation (discussion), demonstration (visual-spatial), interaction (interpersonal-social), contemplation (intrapersonal) or any combination thereof. The aforementioned taxonomy is but one among many offered by different experts in educational psychology and pedagogy. Dr Richard Feldman and Barbara Soloman from North Carolina State University for example, introduced The Index of Learning Styles (2002) consisting of four dimensions of learning styles in which each dimension is a continuum from one's learning preference to another: sensory to intuitive, visual to verbal, active to reflective, and sequential to global.

In spite of developments in educational psychology and improvements in pedagogy, certain cultures are still stuck (if not left behind) in their traditional learning systems. While modern learning systems all over the world have significantly improved by applying meaningful learning, associative learning, and active learning styles which promote bilateral (even multilateral) discussions with fellow students and teachers (acting as facilitators), traditional ones still rely on rote learning, which is basically a memorization technique based on repetition imposed by teachers (acting as infallible gods).

To be fair, rote learning has proven to be effective to master phonics (reading), the periodic table (chemistry), multiplication table (arithmetic), irregular verb conjugation (grammar), anatomy (medicine), even legal cases or statutes (law). The fact that most major religions emerged before the 1439 Printing Revolution—sparked by German blacksmith and printer Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468)—rules out any possibility of religious education beyond rote learning. Initially, Hinduism and Buddhism were spread through oral transmission and rote learning without the existence of text. After all, without printed books, what were other options? In Judaism, Jewish cheders use rote learning to teach the Torah. In pre-Enlightenment Europe, the method of loci (Latin: "places"), was mainly practiced in monasteries and universities, where divinity was taught. (Basically this method is a memory enhancement technique to use visualization in order to organize and recall information. Consecutive interpreters still use this technique to this very day.) Likewise, Muslim madrasas all over the world utilize rote learning to make students memorize the Qur'an. By the way, in the Summer of 2015, several media reported that to honor the holy month of Ramadan, the Islamic State (ISIS) launched a Qur'an memorization competition, with slave girls as prizes.

The rote learning style is still widely practiced in schools across Brazil, China, Greece, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Romania, Turkey, and most Middle Eastern countries. While Gutenberg's invention of mechanical movable type printing had prompted the Renaissance, Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, the Industrial revolution and modern science, pre-Gutenberg rote learning style persists to this very day. Old habits die hard.

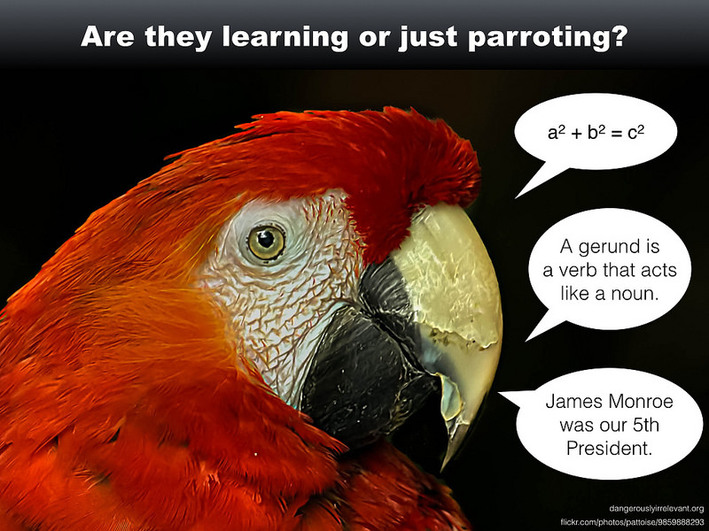

Naturally, rote learning has several drawbacks. Since by default it is based on repetition and comprehension takes a backseat, many educational psychologists regard rote learning as not more than parroting, or regurgitating. Under this system, a student may easily give the wrong impression of having comprehend something merely by saying or writing it. It also appeals to lazy teachers, as rote learning means less work.

Now let's reflect on the side-effect of rote learning in the Middle East, which is today's world hotspot. Interestingly, Arab researchers themselves—not infidels—have stated that rote learning is a "major contributing factor to the lack of progress in science and research and development in the Arab countries." As stated in the United Nations Development Program's Arab Human Development Report (2004): "In Arab educational institutions, curricula, teaching and evaluation methods tend to rely on dictation and instill submissiveness. They do not permit free dialogue and active, exploratory learning and consequently do not open the doors to freedom of thought and criticism. On the contrary, they weaken the capacity to hold opposing viewpoints and to think outside the box. Their societal role focuses on the reproduction of control in Arab societies" (page 147). Furthermore: "Learning comes to be governed by dictation without the learner being educated in, or practicing, freedom" (page 149).

The cruelest irony is that the futility of repetition had long been emphasized by the wise Sufis as illustrated in Learning How to Learn: Psychology and Spirituality in the Sufi Way (1983) by Idries Shah (1924-1996): "The more often you do a thing, the more likely you are to do it again. There is no certainty that you will gain anything else from repetition than a likelihood of further repetition."

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

-SUFI PROVERB

The relentless inclination to ape or imitate among Homo sapiens may be attributed to how one learns in a certain culture. As discussed in Part 23 (Do We Choose a Belief or Does a Belief Choose Us?), statistically speaking, one's religion depends very much on where he or she was born; i.e. a Sunni if born in Afghanistan; a Southern Baptist if in Atlanta; a Catholic if in Buenos Aires; a Hindu if in Mumbai; a Mormon if in Salt Lake City; and so on. The golden rule of real estate (Location, Location, Location) applies.

However, there is still another predictive factor: learning styles. We all learn differently. People who are reared in different cultures also learn to learn different things differently, even if they learn from the same book. All other things being equal, ceteris paribus, even within the same religion, different cultures have different preferred modes of learning, whether by memory (verbal-linguistic), cognition (logical-mathematical), active participation (discussion), demonstration (visual-spatial), interaction (interpersonal-social), contemplation (intrapersonal) or any combination thereof. The aforementioned taxonomy is but one among many offered by different experts in educational psychology and pedagogy. Dr Richard Feldman and Barbara Soloman from North Carolina State University for example, introduced The Index of Learning Styles (2002) consisting of four dimensions of learning styles in which each dimension is a continuum from one's learning preference to another: sensory to intuitive, visual to verbal, active to reflective, and sequential to global.

In spite of developments in educational psychology and improvements in pedagogy, certain cultures are still stuck (if not left behind) in their traditional learning systems. While modern learning systems all over the world have significantly improved by applying meaningful learning, associative learning, and active learning styles which promote bilateral (even multilateral) discussions with fellow students and teachers (acting as facilitators), traditional ones still rely on rote learning, which is basically a memorization technique based on repetition imposed by teachers (acting as infallible gods).

To be fair, rote learning has proven to be effective to master phonics (reading), the periodic table (chemistry), multiplication table (arithmetic), irregular verb conjugation (grammar), anatomy (medicine), even legal cases or statutes (law). The fact that most major religions emerged before the 1439 Printing Revolution—sparked by German blacksmith and printer Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468)—rules out any possibility of religious education beyond rote learning. Initially, Hinduism and Buddhism were spread through oral transmission and rote learning without the existence of text. After all, without printed books, what were other options? In Judaism, Jewish cheders use rote learning to teach the Torah. In pre-Enlightenment Europe, the method of loci (Latin: "places"), was mainly practiced in monasteries and universities, where divinity was taught. (Basically this method is a memory enhancement technique to use visualization in order to organize and recall information. Consecutive interpreters still use this technique to this very day.) Likewise, Muslim madrasas all over the world utilize rote learning to make students memorize the Qur'an. By the way, in the Summer of 2015, several media reported that to honor the holy month of Ramadan, the Islamic State (ISIS) launched a Qur'an memorization competition, with slave girls as prizes.

The rote learning style is still widely practiced in schools across Brazil, China, Greece, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Romania, Turkey, and most Middle Eastern countries. While Gutenberg's invention of mechanical movable type printing had prompted the Renaissance, Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, the Industrial revolution and modern science, pre-Gutenberg rote learning style persists to this very day. Old habits die hard.

Naturally, rote learning has several drawbacks. Since by default it is based on repetition and comprehension takes a backseat, many educational psychologists regard rote learning as not more than parroting, or regurgitating. Under this system, a student may easily give the wrong impression of having comprehend something merely by saying or writing it. It also appeals to lazy teachers, as rote learning means less work.

Now let's reflect on the side-effect of rote learning in the Middle East, which is today's world hotspot. Interestingly, Arab researchers themselves—not infidels—have stated that rote learning is a "major contributing factor to the lack of progress in science and research and development in the Arab countries." As stated in the United Nations Development Program's Arab Human Development Report (2004): "In Arab educational institutions, curricula, teaching and evaluation methods tend to rely on dictation and instill submissiveness. They do not permit free dialogue and active, exploratory learning and consequently do not open the doors to freedom of thought and criticism. On the contrary, they weaken the capacity to hold opposing viewpoints and to think outside the box. Their societal role focuses on the reproduction of control in Arab societies" (page 147). Furthermore: "Learning comes to be governed by dictation without the learner being educated in, or practicing, freedom" (page 149).

The cruelest irony is that the futility of repetition had long been emphasized by the wise Sufis as illustrated in Learning How to Learn: Psychology and Spirituality in the Sufi Way (1983) by Idries Shah (1924-1996): "The more often you do a thing, the more likely you are to do it again. There is no certainty that you will gain anything else from repetition than a likelihood of further repetition."

[To be continued.]

Johannes Tan, Indonesian Translator & Conference Interpreter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed